a Time Machine

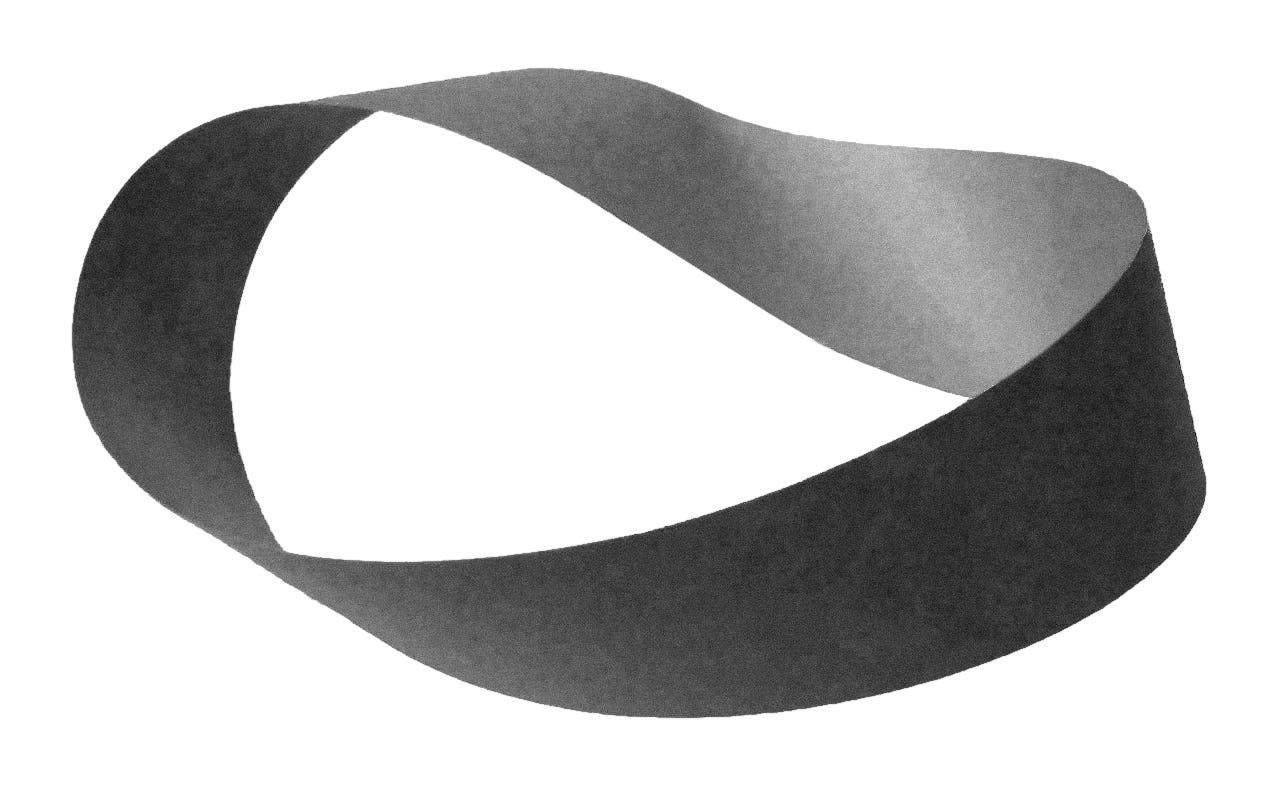

I am on the #2 uptown subway, the express line that goes directly from Times Square to 72nd Street and then on to 96th. Hurtling through time and space, faster and faster. Suddenly everything goes black.

The train comes to a dead halt in the middle of the tunnel. I sit there waiting in the darkness with the other passengers. And then I hear the conductor, speaking over the intercom: “This is the Collective Express.” [crackle, crackle] “There will be a short delay…..”

And then, I hear another voice: “I am now going to tell the story of the creation of the Universe.” Really?

It was a moment before I realized that the voice was my own and that I was sitting there speaking out loud to the other passengers, as though it was a perfectly normal thing to do. I could say I was on acid, but that would be a lie. I could say it was a dream, and that the dream was telling me to create a story that would make sense of everything. Isn’t that what stories are for? But it wasn’t a dream. It was more like a vision.

And then I blacked out. And off I went. When I came to, I got off the train and found myself where I’d begun, on the uptown platform of the #2 express line, at Times Square. How I got there, I’ll never know.

It was freezing. I was in a daze. I walked up the stairs, crossed over to the other side and got onto the downtown local, heading for the Village and home. But I got off again a few stops later, at 19th Street, and found a phone booth — yes, they still had phone booths all over New York way back in 1977. By then, it was almost midnight, but I dialed anyway. Just to hear her voice. She answered. “How are you?”

I hadn’t seen her for 9 years. Until a few nights ago. I was an editor at a documentary company that had just been hired by the Lincoln Center Library for the Performing Arts to record Meredith Monk’s theater “opera,” Quarry, which even back then was considered a seminal work in the history of 20th-century theater. And since I was the one who would be putting it together in the editing room, for posterity, my boss told me to go and see it for myself. So off I went.

And there she was, center stage, right in front of me, just like I’d last seen her, before she closed the door and left me standing in the dark.

Her voice rang out through the theater. “R E A L L Y?” That’s what she said. Really.

A few years later, around 1983, I tried to make my subway vision a reality. I bought a computer, a DEC Rainbow, for $3k. I sat there wondering what I could do with it, other than keep the books for my own little film company on a “spreadsheet.” The computer had a “memory” — 128 kilobytes of Random Access Memory, so you could access data instantly, non-sequentially, no matter its actual location, just like in your mind — and a hard drive with a whopping 5 megabytes! of storage memory. What could all of that memory be used for?

To remember, of course! Not just what had happened to me on my train ride, but to everyone, everywhere. What if you could take people on a trip through Time, on a kind of collective express, and tell a Creation Story? So that people would understand where we came from, and how we all got here, and where it was all going.

It would be a kind of “adventure game,” a journey from a first-person perspective, where you had to decide where to go next, the future always somewhere up ahead. The first of its genre appeared in 1975 on a computer at Stamford that shared a link with a handful of other university mainframes — computers SO big that each had its own room — on ARPANET, the first network in cyberspace. In fact, it was cyberspace. The game was called Colossal Cave Adventure, based on a map of the Monmouth cave system in Kentucky. But all it had was a description. “YOU ARE INSIDE… A WELL HOUSE FOR A LARGE SPRING. THERE ARE SOME KEYS ON THE GROUND. A SHINY BRASS LAMP IS NEARBY…”

It was dark down there. You had to use your imagination, as you went from one place to another.

Back then there wasn’t any way to show drawings or maps on a computer screen. Even text was new and only in UPPERCASE. Before that, there were only squiggles on a cathode ray tube and before that you had to punch holes in a card with a special typewriter and to see what you’d “written,” you had to monitor a panel with dozens of light bulbs — which is why computer displays were once called “monitors.”

The idea for punch cards? Well, that came from IBM, which got it from a guy who used them to record the 1890 census. And that idea went all the back to 1801 when M. Jacquard tied a bunch of them together in a sequence to control the patterns his loom created on cloth. And that idea went back to 1725 when it occurred to another Frenchman that it might be possible to automate the tedious process of raising and lowering a single warp thread on a loom depending on whether or not a paper tape had a hole in it. [O or 1]

Before then, weavers had to remember the pattern, and raise and lower the warp over and under the weft by hand. The more complex the pattern, the harder it was to remember what came next. Just as in the ancient Art of Memory, invented by the Greeks before orators wrote their speeches down — the more complex your argument, the easier it was to lose the thread, so to speak. Like in a Labyrinth. [hang on, the trip is almost over]

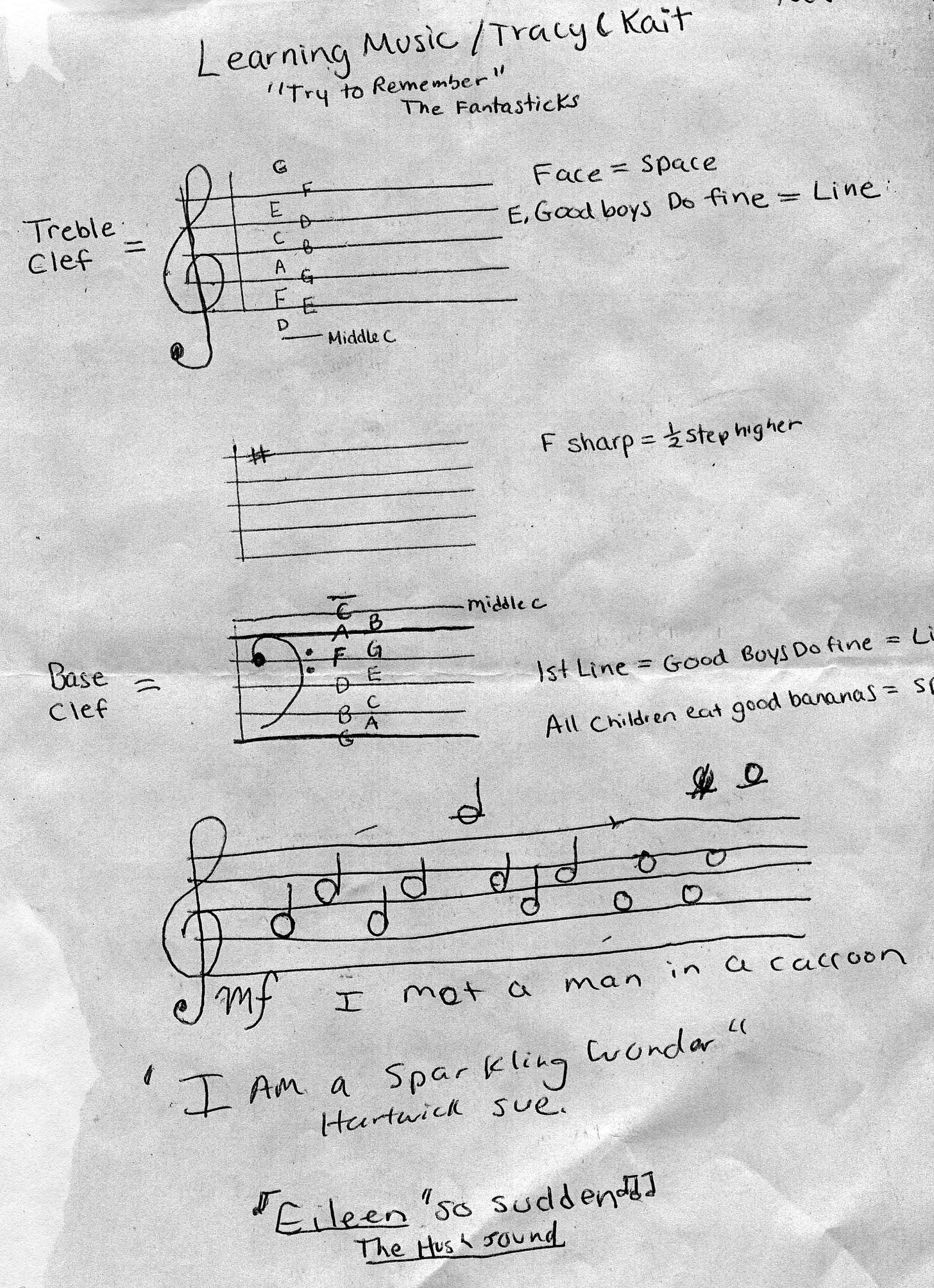

There had to be some way to connect one Idea to the next, so that when you came to the end of one idea, the next would be recalled spontaneously, without conscious effort. That’s when someone discovered that you could recall your thoughts much more easily if you imagined yourself moving through a physical space, like a palace with many rooms (or a cave with many caverns). Each time you came to a new thought, you linked it to a picture of an object in a new room. The more striking the image the better, like a blue bull or a god standing on his head. Then all you had to do was retrace your steps through the palace, and each picture would re-mind you of the Idea to which it was linked. One link would lead to another, in a chain of visual metaphors. [breathe]

With the gradual adoption of the written word, the art of constructing Memory Palaces fell into disuse and was all but forgotten, surviving only in a few Greek and Roman texts about rhetoric (and in the locution, “in the first place,” etc.) But when these finally became widely available again with the advent of printing late in the fifteenth century, it wasn’t just an argument that needed reconstruction, it was an entire world of knowledge and experience, lost for over a millennium. [relax, you’re almost there, at the end of the ride]

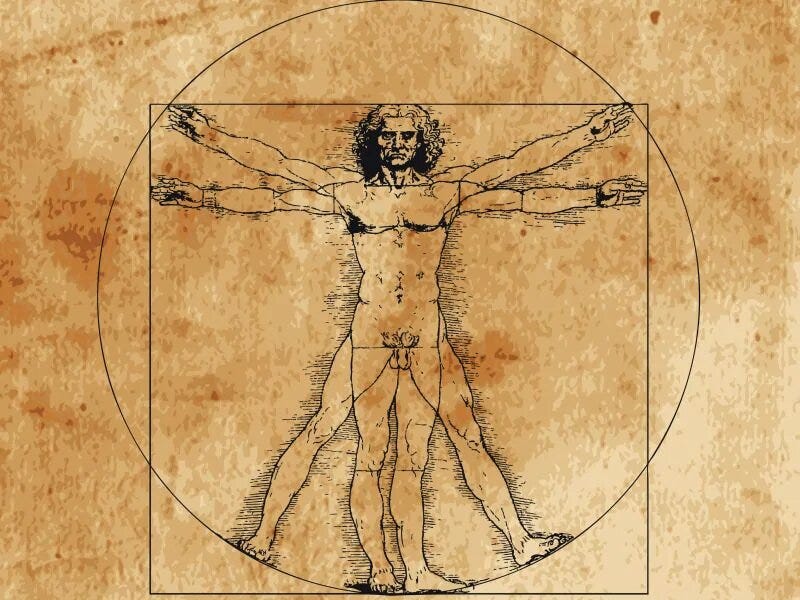

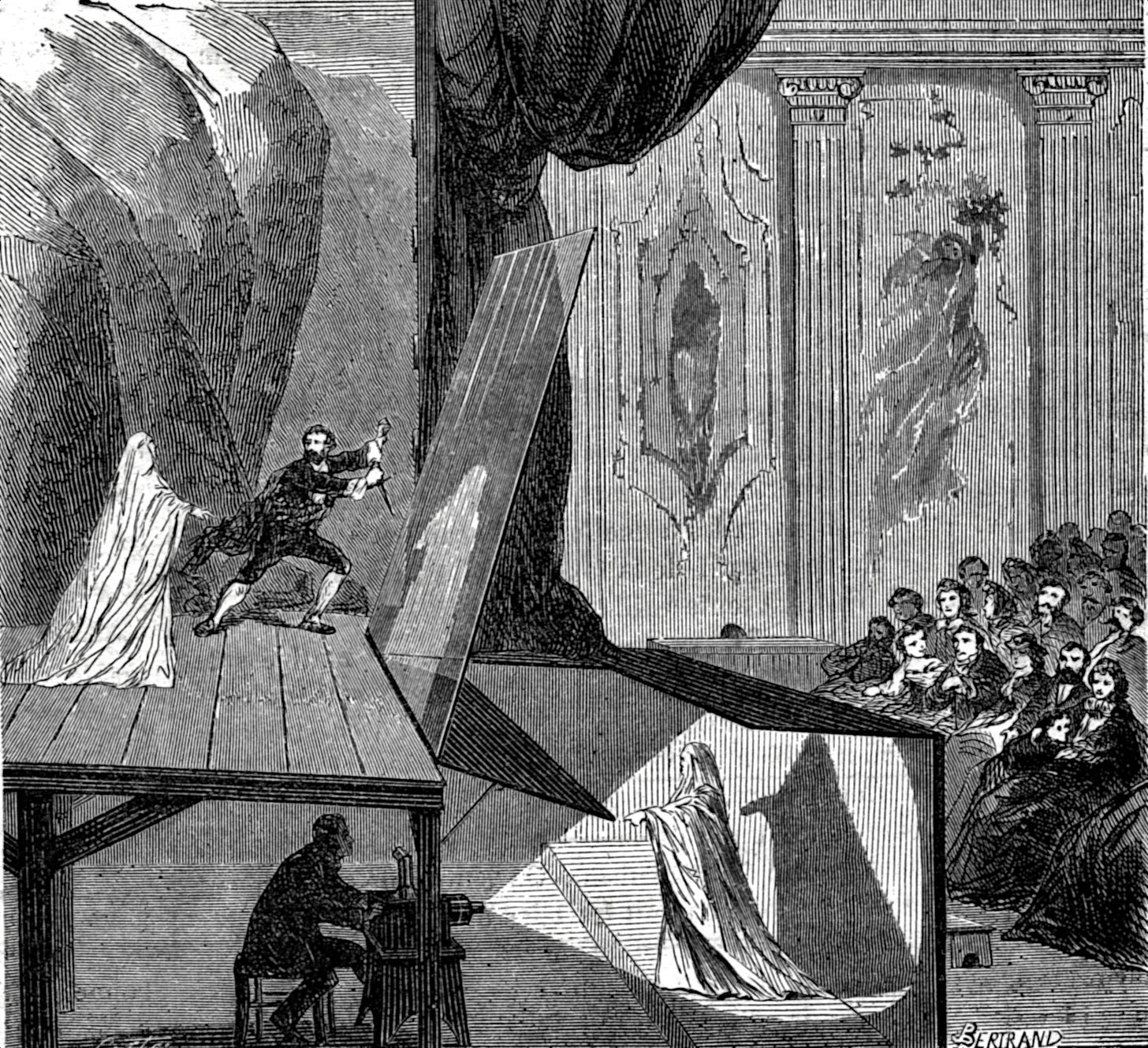

The Art of Memory underwent a radical transformation. The Memory Palace became a theater in which to re-enact the past, to recover not only ancient texts, but their hidden order and meaning. Memory Theaters were erected — some were actual physical structures — containing a set of symbolic images (archangels, signs of the Zodiac, mythological heroes) and writings drawn from Greek and Hebrew sources (Aristotle, Plotinus, the Kabbalah), all carefully selected to induce in the spectator a state of Enlightenment.

But spectator is perhaps a misnomer, for the visitor to a Memory Theater was really its star, its sole performer. Standing at center stage, with the emblems and texts arranged in a tiered semi-circle, each visitor ‘performed’ an act of contemplation, the order of the images and words reflecting the order of the cosmos, which, in turn, reflected the order of the perfected human spirit. A spiritual reawakening. A Renaissance. Ta-da!

Just like the book I am writing. Another Memory Theater.

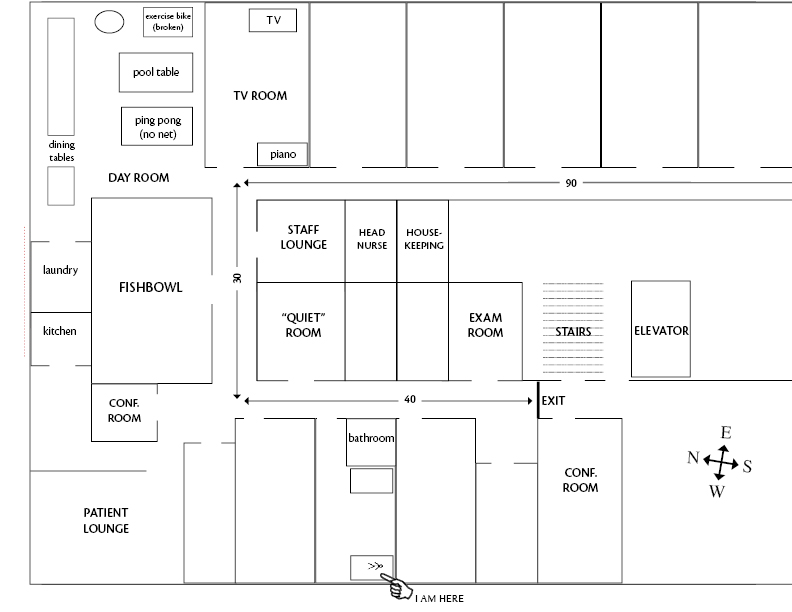

I’d already acquired some experience constructing a universe on the floor of my bedroom so as to locate myself within its space. Now I wanted to see if it was possible to make a model for everyone, to locate us all in time, to renew a link with the great urban civilizations of the past, just as all those humanists of the Renaissance had attempted to do.

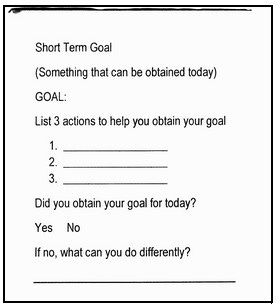

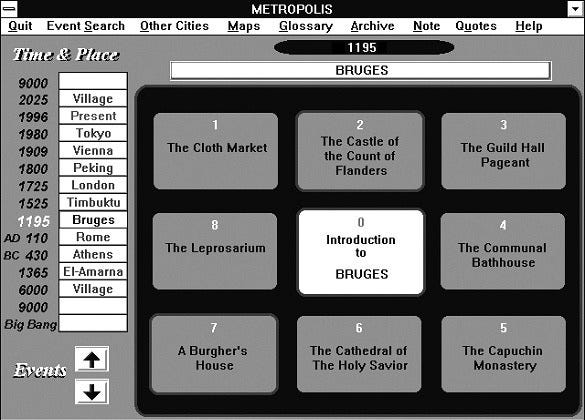

I played around with several ideas. Perhaps a big clock? Then I tried a Shakespearean model, a Globe Memory Theater in the round, a series of concentric circles, beginning with a Neolithic village, and spreading outward, like ripples in a pond, or planets in a solar system, with Athens (430 BC) and Rome (AD 110) or a medieval city (Bruges about 1200) arranged in a widening arc. But I soon abandoned this in favor of my original vision, a subway line, with express stops arranged vertically, my Neolithic Village at the bottom and the Global Village of 2025 at the top, extending further into an unknown future.

Click on an urban button and you’re given a choice of eight locations to explore — a visit to the Count of Flanders’ castle in Bruges, a chance to be part of a pageant put on by the various town guilds, a trip to the bathhouse or a Capuchin monastery — each location in every city loosely representing a common theme: Commerce, Power, Public Spectacle, Social Interaction, Knowledge, Faith, Domestic Life, Exclusion. A shared vision of communal space at a moment in time, stacked one on top of each other, an evolving space/time.

Click on the Up or Down buttons at the lower left and you can move forward or backward between two urban centers, making local stops at significant events or cultural trends — the rise of the Hopewell Indian cultures in America (AD 150); the development of the Noh play in Japan (1375); the invention of double-entry bookkeeping in Italy (1390); the first minute hands on watches (1671); the goose-step is introduced in Prussia (1698); price tags appear in Western Europe (1700); canned food is invented (1810); the appearance of paperback novels in England (1850); the first state law to make wife-beating a crime (1890); the theory of continental drift (1912); Disneyland opens (1955); the first artificial brain transplant? (2250) — about 2000 in all, each represented by a slide. You could even add your own. “My grandfather arrives in America (1905)”.

Hold one of the arrow buttons down, instead of just clicking, and off you go, as though you’d stepped on the gas, the slides zooming past the window like a flip book or a time-lapse movie, images of clothing and buildings and inventions and wars flying by, faster and faster, all evolving or devolving, cycling back and forth as though you were at the controls of a Time Machine, like the driver of the Victorian contraption in the 1895 novel by H. G. Wells, itself one of the events.

The goal: to allow you to weave your own path through Time — unmediated by second-hand texts that impose some rigid interpretative schema or wall everything off into separate disciplinary categories — so the inter-relationships and larger connections can be experienced directly, a fresh take.

In order to create a prototype of my Memory Theater, I spent a year teaching myself Turbo Pascal, one of the first programming languages for personal computers (by now long extinct), and after another 2 years, I rented a car and lugged my Rainbow (now extinct) down to Washington to give a demo to a panel at the “Division of Exemplary Projects” (extinct) of the National Endowment for the Humanities. I was given $60k, most of which went to pay for another panel — distinguished professors (almost all extinct) to supervise the creation of “appropriate” content. Two years after that, another grant came from FIPSE — the Fund for the Improvement of Post-Secondary Education, a division of the U.S. Dept. of Education (soon to be extinct).

Alas, all to no avail. As fast as I ran to make METROPOLIS into a usable program that would fit on a set of CD-ROM discs, everything else ran faster still. While I and my panel plotted the course of Civilization, as though we were outside time, the WorldWideWeb overtook CD-ROMs and METROPOLIS and the past, leaving it all behind in a cloud of dust.

Faster and faster, hurtling through time and space. This is the Collective Express.